In 1913, B.R. Ambedkar arrived in New York City from Bombay at the age of twenty-two, on a scholarship to attend Columbia University that Fall and pursue an M.A. in Economics. After returning to India (not before completing a Ph.D. in London), Ambedkar would go on to become the most influential Dalit leader in India in the 20th century, the chairman of the constituent assembly that drafted the Indian constitution, and one of the most incisive theorists of caste and greatest intellectuals of modern India. From the perspective of a researcher, Dr. Ambedkar's proximity to Harlem during his years of study at Columbia has always raised several questions about his experience in the U.S. How might have his experiences in New York impacted his thinking? Aside from his influential mentors at the University (John Dewey, Edwin Seligman, James Shotwell, and James Harvey), who were his personal acquaintances in the U.S.? And did his experience witnessing anti-Black racism in America influence his thinking on the caste question in India? Despite the many allusions to race in the U.S. in his oeuvre, Ambedkar -- as far as I know -- left no first hand account of his time in New York to answer such questions.

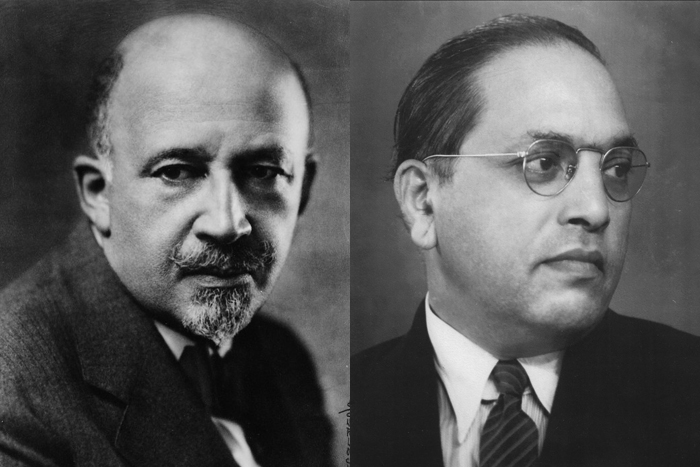

An interesting record appears in the papers of W.E.B. Du Bois, the prominent African American intellectual and activist, whose archive is housed at the University of Massachusetts. In the 1940s, Ambedkar contacted Du Bois to inquire about the National Negro Congress petition to the U.N., which attempted to secure minority rights through the U.N. council. Ambedkar explained that he had been a "student of the Negro problem," and that "[t]here is so much similarity between the position of the Untouchables in India and of the position of the Negroes in America that the study of the latter is not only natural but necessary." In a letter dated July 31, 1946, Du Bois responded by telling Ambedkar he was familiar with his name, and that he had "every sympathy with the Untouchables of India."

As other commentators have pointed out, Du Bois had long been fascinated with India’s role as a harbinger of anticolonialism.1 He had befriended Indian "Home Rule League" nationalist Lajpat Rai, during the latter’s exile in the U.S. between 1914 and 1919. Du Bois' interest in India turned up in editorials of the N.A.A.C.P.-issued magazine The Crisis over the decades, as well as the novel Dark Princess published in 1928. For Du Bois, the cause for Indian independence was one facet of a larger movement to undo the color line that belted the world. Du Bois’ correspondence with Ambedkar, however, does not appear to extend beyond this letter.2

The analogy between the caste system and racism in the U.S., on the other hand, has a much longer and sustained history. In 1873, Jotirao Phule, an important social reformer in Maharashtra, began his polemical Gulamgiri (Slavery) with a dedication to American abolitionists "in an earnest desire that my countrymen may take their example as their guide in the emancipation of their Sudra Brethren from the trammels of Brahmin thralldom."3 Nearly a hundred years later, an organization led by Dalit artists and activists named themselves the "Dalit Panther," in reference to the Black Panthers in the U.S. In their manifesto, issued in 1971, the Panthers wrote: "From the Black Panthers, Black Power was established. We claim a close relationship with this struggle."4

In honor of Dalit history month this April, we wanted to highlight this brief but important historical exchange in the archives between two important leaders in the global struggle against the systems of racism and caste.

[Special thanks to Professor Gary Tartakov for scanning and sharing these documents, and Robert Cox of the W.E.B. Du Bois Library at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst for allowing us to post them.]

1. Several books have highlighted this history, including most recently Gerald Horne’s End of Empires (2008), Dohra Ahmad’s Landscapes of Hope (2009), and Nico Slate’s Colored Cosmopolitanism (2012). Kamala Visweswaran's Un/common Cultures (2010) contains two chapters on the work of Ambedkar and Du Bois, with reference to their correspondence.

2. For further reading on the Ambedkar-Du Bois correspondence, see Kapoor, S.D. "B.R. Ambedkar, W.E.B. Du Bois and the Process of Liberation" Economic and Political Weekly 38.51-52 (2003): 5344-5349, and Immerwahr, Daniel. “Caste or Colony? Indianizing Race in the United States” Modern Intellectual History 4.2. (2007): 275-301.

3. Prashad, Vijay. The Karma of Brown Folk. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000. 26.

4. Limbale, Sharankumar. Dalit Panthar. Pune: Sugava Prakashan, 1989. 260.

Manan Desai teaches at Syracuse University and serves on the Board of Directors for the South Asian American Digital Archive.