The Barbour Scholarship

Early International Presence at the University of Michigan

By Dashini Jeyathurai |

FEBRUARY 14, 2012

the rationale behind a scholarship program that was to support the educational advancement of women from the Orient. Barbour wrote, “The idea of the Oriental girls’ scholarships is to bring girls from the Orient, give them an Occidental education and let them take back whatever they find good and assimilate the blessings among the peoples from which they come” (Rufus 15). During his travels to Japan and China, Barbour had the opportunity to meet with three East Asian women who had been trained in medicine at the University of Michigan in the 1890s. Impressed by the kinds of work these women were doing, Barbour was inspired to create a scholarship that would allow other women from that part of the world to do the same. For its time, it should be no surprise that the discourse surrounding the scholarship was inflected by a rhetoric of uplift. As illustrated below, a Western education was seen to be key to emancipating these women:

the rationale behind a scholarship program that was to support the educational advancement of women from the Orient. Barbour wrote, “The idea of the Oriental girls’ scholarships is to bring girls from the Orient, give them an Occidental education and let them take back whatever they find good and assimilate the blessings among the peoples from which they come” (Rufus 15). During his travels to Japan and China, Barbour had the opportunity to meet with three East Asian women who had been trained in medicine at the University of Michigan in the 1890s. Impressed by the kinds of work these women were doing, Barbour was inspired to create a scholarship that would allow other women from that part of the world to do the same. For its time, it should be no surprise that the discourse surrounding the scholarship was inflected by a rhetoric of uplift. As illustrated below, a Western education was seen to be key to emancipating these women: Only one scholar came directly from the Indian purdah. She was accompanied from her seclusion to the secretary’s office by an uncle; during the first interview, in spite of many attempts to hear her voice, the secretary could distinguish only a faint response, and she looked up but once. Not long afterward, she was a free individual able to say that her soul was her own (Rufus 25).

While the perception that a Western education would liberate such women was not unusual, what was striking was Barbour’s hope that they would prevent future international conflicts. In a letter to Helen Hatch in 1917, he wrote, “If a thousand Japanese girls could be educated in the United States to be physicians and teachers and returned to Japan to ply their work, we certainly never would have any war with Japan…and I think the same is true of other Oriental countries” (Rufus 39). The scholars were imagined to be emissaries of peace.

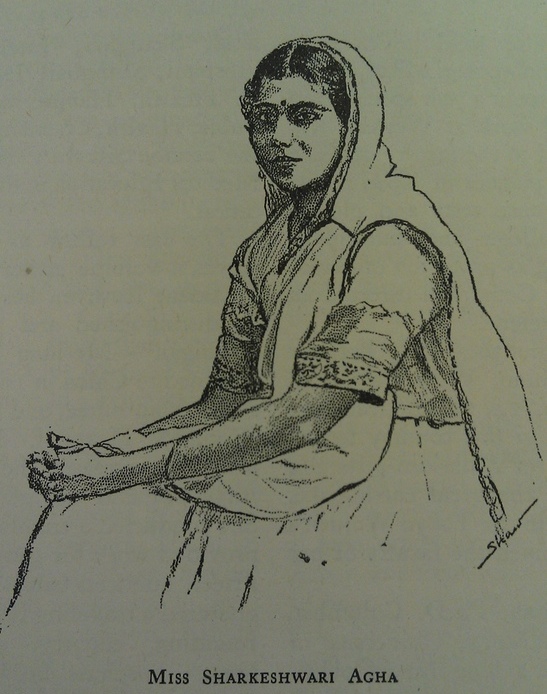

The scholarship’s first recipients were two Japanese women who arrived in 1914 before the initiative was officially announced. Not only did they live with the Barbours, they were tutored for several months to improve their English and better prepare them for their time at the university. However, the profiles of Barbour scholars became increasingly impressive as more individuals sought out the opportunity. For example, 1928-1929 saw seventy-five applicants from India. Among them was "a young woman from a high-class Kashmiri Brahmin family, with a B.A., M.A., and L.L.B. from the University of Allahabad, who was the principal of a high school (19)."

Apparently, when the adjudicating committee saw Miss Shakeshwari Agha’s photograph, the decision was unanimous. It is hard to tell whether this simply meant that the committee was so familiar with her person that she immediately outstripped the rest of the competition or if there was something about her physiognomy that convinced them of her scholarly virtues! Regardless, Agha would spend two years at Michigan where she specialized in education and received a second M.A before becoming the head of the Teacher Training Department of Crosthwaite College for Women, Allahabad. She would also take on the position of secretary for the All-India Women’s Conference for Education and Social Reform.

Apparently, when the adjudicating committee saw Miss Shakeshwari Agha’s photograph, the decision was unanimous. It is hard to tell whether this simply meant that the committee was so familiar with her person that she immediately outstripped the rest of the competition or if there was something about her physiognomy that convinced them of her scholarly virtues! Regardless, Agha would spend two years at Michigan where she specialized in education and received a second M.A before becoming the head of the Teacher Training Department of Crosthwaite College for Women, Allahabad. She would also take on the position of secretary for the All-India Women’s Conference for Education and Social Reform. Yearly updates on the activities of Barbour Scholars indicated that more than a few of them took thorough advantage of their time in the United States to actively engage with the communities around them as well as with other international students in the country. A 1931 Barbour Scholars Newsletter reports that M.A. candidate Kapila Khandvala was a delegate at a conference of students in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, As exciting as it must have been for these early Barbour scholars, their experiences as international students were not without challenges.and was planning to attend the Oriental Students’ Conference in Chicago later that year. In 1946, not only did Leela Desai preside over the Hindustan Association in Ann Arbor, she went on a lecture circuit arranged by the National Board of the YWCA where she visited other Midwestern universities.

As exciting as it must have been for these early Barbour scholars, their experiences as international students were not without challenges. At the time, living as a Barbour scholar meant adapting to fairly strict rules especially for women who had held positions of authority as teachers or administrators in their countries of origin. In Carl Rufus’s "Twenty-Five Years of the Barbour Scholarships," he recalled two women who struggled to acclimatize to their new lives at the university.

A Barbour Scholar with her own ideas about student life and outside political activity was warned by the Dean of Women several times. At a final showdown, she could not understand why she could not be allowed to continue, reminding the dean that she was not obeying the Christian injunction to forgive seventy times seven (23).

Another Barbour Scholar found it difficult to become adjusted to American food and to dormitory life. The first fall she wished to cook her own food and to live her own way. When thwarted, she became hysterical and even threatened suicide. The frightened dormitory head took it to the dean’s wife and together they came to a called meeting of the committee. The chairman and the perplexed deans listened to the story, the crux of which was that the girl decided to go to New York during the vacation… She went, spent a pleasant vacation with friends, returned safely, and the incident was closed, as she became better adjusted and more co-operative (23-24).

While there’s no evidence that any of the Barbour Scholars prevented international conflicts as Barbour had hoped, some of the women found themselves in the thick of World War II and its aftermath. One of the most illustrious Barbour Scholars, Dr. E.K. Janaki reported back in the 1941 Barbour Scholars newsletter, "I am still alive in London and getting along with my work as well as one could. I have just come back from Edinburgh where I went for a rest after months of broken sleep.

This part of London has had a lot of bombing (11)." Janaki would become the first Indian woman to hold a chair in a university for men in India. In 1943, Dr. Chieko Otsuki would send a long description of her own work as a laboratory technician in the main hospital of a Japanese internment camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming.

This part of London has had a lot of bombing (11)." Janaki would become the first Indian woman to hold a chair in a university for men in India. In 1943, Dr. Chieko Otsuki would send a long description of her own work as a laboratory technician in the main hospital of a Japanese internment camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming. This collection of correspondences and other forms of ephemera give us some insight into the multi-faceted lives of the young women who took up both the exciting and terrifying opportunity that Levi Barbour offered them. The Barbour Scholarship continues to be administered through the University of Michigan’s Rackham Graduate School.

Many thanks to the University of Michigan’s Bentley Historical Library for permission to use images from the records of the Barbour Scholarship for Oriental Women Committee.

Works Cited

• Rufus, Carl. "Twenty-Five Years of the Barbour Scholarships." Michigan Alumnus Quarterly Review 49.11 (December 1942).

Dashini Jeyathurai grew up in Malaysia and Singapore before moving to the United States to pursue her B.A. in English at Carleton College. She is now a doctoral candidate in English and Women’s Studies at the University of Michigan.