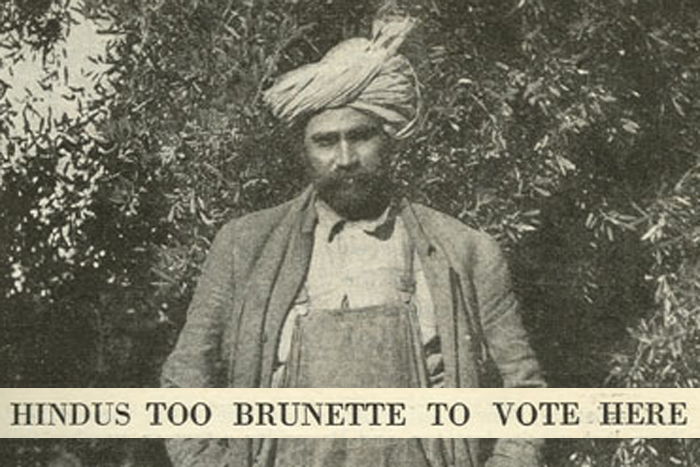

Hindus Too Brunette To Vote Here

FEBRUARY 19, 2015

On this day in 1923 (February 19), the U.S. Supreme Court decided unanimously to bar South Asians from becoming American citizens and to denaturalize those who had already done so in the landmark decision, United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind. Thind, who immigrated to the United States in 1913 and even trained

at Camp Lewis in Washington to fight with the U.S. Army in World War I, had begun his personal struggle for citizenship five years earlier, in 1918. Through its decision, the Supreme Court quashed the hopes of Thind and fellow South Asians in the United States to gain full recognition as American citizens. It was not until 1946, more than two decades later, that South Asians were again allowed the right of citizenship.

at Camp Lewis in Washington to fight with the U.S. Army in World War I, had begun his personal struggle for citizenship five years earlier, in 1918. Through its decision, the Supreme Court quashed the hopes of Thind and fellow South Asians in the United States to gain full recognition as American citizens. It was not until 1946, more than two decades later, that South Asians were again allowed the right of citizenship.An article published in the Literary Digest, "Hindus Too Brunette To Vote Here," provides an explanation of the racial logic behind the Supreme Court decision.1 The issue at hand was what was meant by “white.” Thind, and many others, argued that according to the "racial science” of the day, South Asians were descendants of Indian Aryans who belonged to the “Caucasian race.” Using this racial algebra, Thind too was “white” and thus eligible for citizenship.2 The Supreme Court responded:

“It would be obviously illogical to convert words of common speech used in a statute into words of scientific terminology when neither the latter nor science, for whose purpose they were coined, was within the contemplation of the framers of the statute are to be interpreted in accordance with the understanding of the common man, from whose vocabulary they were taken.”The Supreme Court further concluded that the Hindu “is of such character and extent that the great body of our people instinctively recognize it and reject the thought of assimilation.” Moreover, the Court struck against the racial logic that Thind had utilized, citing that the term “Aryan” indicated a “common linguistic root buried in remotely ancient soil” which was “inadequate to prove common racial origin.”

As the scholar Ian Haney-Lopez has written, the Thind decision powerfully redrew the parameters of citizenship, of race, and of whiteness. He writes, “the Court stanched the collapsing parameters of Whiteness by shifting judicial determinations of race off of the crumbling parapet of physical difference and onto the relatively solid earthwork of social prejudice."4 Other commentators, like Sucheta Mazumdar, have been more critical of the sort of reasoning adopted by Ozawa, Thind and other Asian migrants to the U.S., pointing out that their strategies challenged racial exclusion by investing in “whiteness” instead of challenging a color line which systematically discriminated against all non-white people.3 One sees in these Supreme Court cases what George Lipsitz calls the “possessive investment in whiteness,” that is, the structural and material benefits that have historically and contemporaneously been accrued to whites in the U.S. Thind’s case, clearly, shows us the challenges and negotiations faced by South Asians during this period.

Thind, however, continued to live in the U.S., receiving a Ph.D. at Berkeley, and eventually receiving his citizenship in 1936 after Congress

had decided that veterans of World War I should be eligible for naturalization.5 In 1940, Thind eventually married his wife Vivian, who herself became an active member in the Indian-America Society, and he continued to lecture across the country on issues of non-violence, spirituality, and metaphysics; he passed away in 1967.

had decided that veterans of World War I should be eligible for naturalization.5 In 1940, Thind eventually married his wife Vivian, who herself became an active member in the Indian-America Society, and he continued to lecture across the country on issues of non-violence, spirituality, and metaphysics; he passed away in 1967.1. It is important to note that the term 'Hindu' in the article is meant as a racial classification, not a religious one.

2. A similar case occurred months earlier, when Takao Ozawa, developed a phenotypical argument, stating that being Japanese, his skin was just as white than the average white person. The Supreme Court ruled against him.

3. The spectre of Blackness is evident in the decision, as the Justice Sutherland concludes how linguistic commonalities do not prove racial commonality: “Our own history has witnessed the adoption of the English tongue by millions of negroes, whose descendants can never be classified racially with the descendants of white persons.”

4. Lopez, Ian Haney. White by Law: The Legal Construction of Race. New York: NYU Press, 1997. 67.

5. Chi, Sang and Emily Moberg Robinson. Voices of the Asian American and Pacific Islander Experience. Santa Barbara: Greenwood, 2012. 339.