As a gift for her two little girls, [Helen Bannerman] wrote and illustrated The Story of Little Black Sambo (1899), a story that clearly takes place in India (with its tigers and ‘ghi,’ or melted butter), even though the names she gave her characters belie that setting. For this new edition of Bannerman’s much beloved tale, the little boy, his mother, and his father have all been given authentic Indian names: Babaji, Mamaji, and Papaji.

Printed within a minaret-shaped column on its dust jacket, these lines preface one’s reading of Harper Collins’ children’s book The Story of Little Babaji (1996).

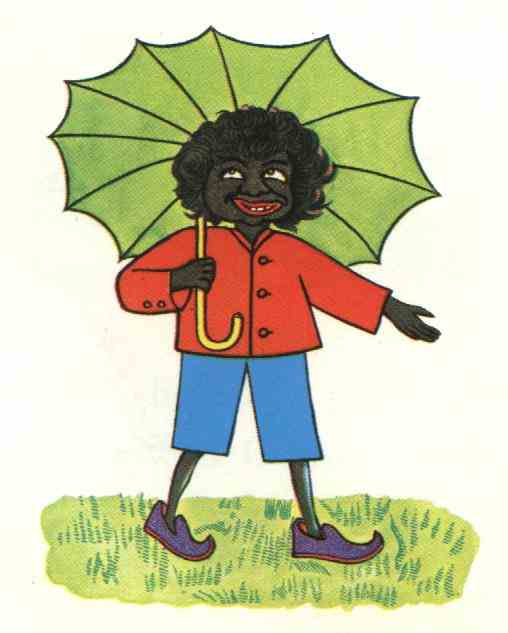

The neatly packaged narrative that the dust jacket offers belies the fraught history of Bannerman’s original text, The Story of Little Black Sambo. Published first in England in 1899 and then in the United States the following year, it tells the story of a little boy who is forced to surrender his clothing and his umbrella to four tigers so as to avoid being eaten by them. However, it is Little Black Sambo who has the last laugh when the tigers begin fighting among themselves and ultimately chasing each other around a tree until they are transformed into a pool of ghee. Not only does he recover his possessions, his mother, Black Mumbo, uses the ghee to make pancakes for the entire family. In fact, in the French-language edition of Bannerman’s book, Sambo Le Petit Négre (1948), the little boy is depicted eating tiger-striped pancakes!

The neatly packaged narrative that the dust jacket offers belies the fraught history of Bannerman’s original text, The Story of Little Black Sambo. Published first in England in 1899 and then in the United States the following year, it tells the story of a little boy who is forced to surrender his clothing and his umbrella to four tigers so as to avoid being eaten by them. However, it is Little Black Sambo who has the last laugh when the tigers begin fighting among themselves and ultimately chasing each other around a tree until they are transformed into a pool of ghee. Not only does he recover his possessions, his mother, Black Mumbo, uses the ghee to make pancakes for the entire family. In fact, in the French-language edition of Bannerman’s book, Sambo Le Petit Négre (1948), the little boy is depicted eating tiger-striped pancakes!

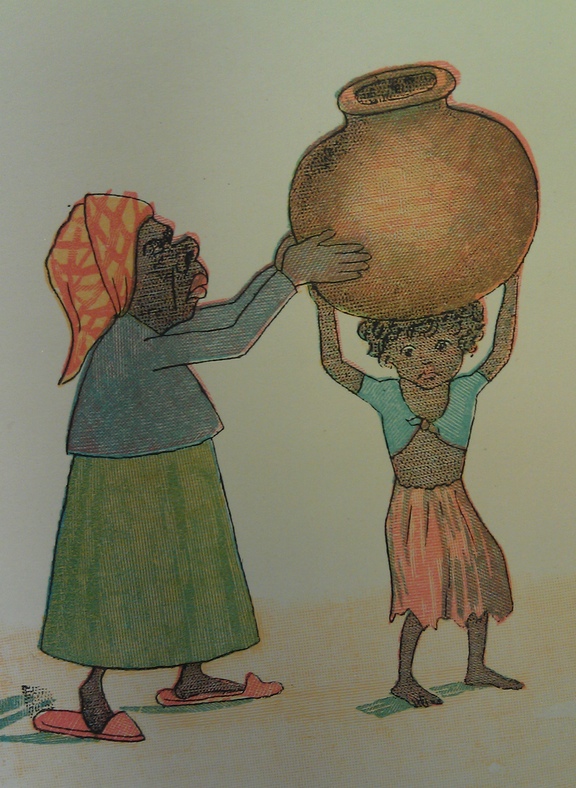

Bannerman herself was no stranger to India. As a wife of an Indian Medical Service officer, Bannerman spent more than thirty years in Madras and made frequent trips to Kodaikanal. If we were to focus simply on the textual narrative of The Story of Little Black Sambo, there is no doubt that Bannerman’s protagonist is an Indian child navigating an Indian landscape. And if we were to look at Bannerman’s other works such as The Story of Little Black Mingo (1900), once again, the textual narrative is replete with evidence that this tale is also set in India. In The Story of Little Black Mingo,

the girl protagonist must contend with a “mugger” (a crocodile specific to the Indian subcontinent) that is conspiring to eat her whenever she carries the “chatty” that the “dhobi” uses to the river.

the girl protagonist must contend with a “mugger” (a crocodile specific to the Indian subcontinent) that is conspiring to eat her whenever she carries the “chatty” that the “dhobi” uses to the river. While there was nothing particularly startling about Bannerman’s plot, it was the illustrations accompanying the narrative that garnered the attention of American civil rights activists in the 1930s and 1940s. In various editions of the book, Sambo is depicted as having very dark skin that is juxtaposed against the whites of his eyes and teeth, a broad nose, and a wide smile. While set in India and about an Indian protagonist, the illustrations matched what African-Americans such as Langston Hughes recognized immediately to be the “pickaninny.” In Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights (2011), Robin Bernstein writes, “The pickaninny was an imagined, subhuman black juvenile who was typically depicted outdoors, merrily accepting (or even inviting) violence” (34). In response to the suggestion that Bannerman’s book was nothing more than a simple children’s story, Hughes would cut to the quick of American race relations saying that Little Black Sambo was “amusing undoubtedly to the white child, but like an unkind word to one who has known too many hurts to enjoy the additional pain of being laughed at” (Qtd. in Pilgrim).

Additionally, the term “Sambo” had already gained currency in America as a black archetype, particularly, a black servant who was “loyal and contented” (Pilgrim). This was by no means limited to the United States. In 1974, a West Indian factory worker in Britain charged with assaulting his co-worker for calling him “Sambo” was informed by the presiding judge that “Sambo” was nothing more than a playful term used between workmates and hardly justified assault (Dunkling 215).

Additionally, the term “Sambo” had already gained currency in America as a black archetype, particularly, a black servant who was “loyal and contented” (Pilgrim). This was by no means limited to the United States. In 1974, a West Indian factory worker in Britain charged with assaulting his co-worker for calling him “Sambo” was informed by the presiding judge that “Sambo” was nothing more than a playful term used between workmates and hardly justified assault (Dunkling 215). The tumultuous history of Bannerman’s The Story of Little Black Sambo exceeds the tidy narrative provided by the dust cover of The Story of Little Babaji that is seen as a corrective for that original text. Unknowingly, the circulation of Bannerman’s text placed a narrative born out of Britain’s imperialist presence in India firmly within the landscape of U.S. civil rights activism and racial politics.

Many thanks to the University of Michigan’s Special Collections Library for permission to use the images seen in this post and a special thanks to the staff who were tremendously helpful in procuring these materials.

Works Cited

• Bannerman, Helen. The Story of Little Black Mingo. London: Nisbet & Co. Ltd., 1900.

• Bannerman, Helen, and Gustaf Tenggren. Sambo Le Petit Nègre. Paris: Cocorico, 1948.

• Bannerman, Helen. The Story of Little Babaji. New York: Michael de Capua Books, 1996.

• Bernstein, Robin. Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood From Slavery to Civil Rights. New York: New York University Press, 2011.

• Dunkling, Leslie. A Dictionary of Epithets And Terms of Address. London: Routledge, 1990

• Pilgrim, David. “The Picaninny Caricature.” Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia. October 2000. Ferris State University. March 30, 2012 Read online

Dashini Jeyathurai grew up in Malaysia and Singapore before moving to the United States to pursue her B.A. in English at Carleton College. She is now a doctoral candidate in English and Women’s Studies at the University of Michigan.