Chandra Dharma Sena Gooneratne, a graduate student at the University of Chicago in the 1920s, is a fascinating if also mysterious figure in SAADA’s archive. As a student in Hyde Park, he served as the captain of the Varsity Polo Club and was a member of the ROTC, all the while completing an M.A. and Ph.D.1 One source described him as an Indian from an "old high-caste family with several landed estates,"2 while another describes his time serving with British Forces in World War I in Mesopotamia, Persia, and Flanders.3 While in the U.S., he lectured on the Chautauqua circuit, which took him across different towns around the Midwest in the late 1920s and the early 1930s. The topics of his lectures ranged from figures like Tagore and Gandhi to the cause for Indian independence and the need to abolish the caste system. Reporters covered not only the content of his lectures, but spent a great deal of print on the exotic impression he left on his audience. An Ohio newspaper described Gooneratne as "beautifully clothed in his native garb," and commented on his "magnetic […] hold on his audience."4

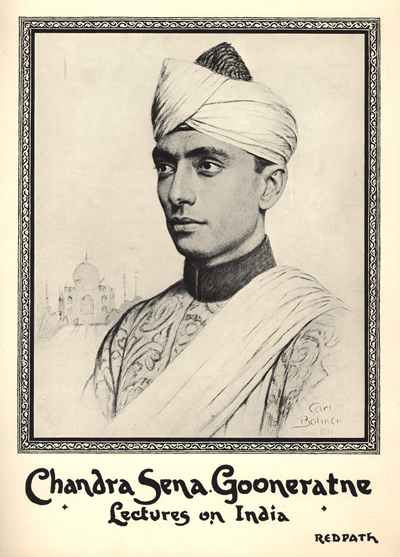

Several newspapers echoed that sentiment, describing Gooneratne’s "magnetic influence,"5 and "magnetic personality" which left attendees "spellbound."6 The imagery used to promote Gooneratne's lectures drew on existing stereotypes of India (note the Taj Mahal pictured on the pamphlet), and so too did the language used to describe him: "Magnetic," for instance, was a term partially associated with the American middlebrow fascination with the occult powers of Hindu yogis.

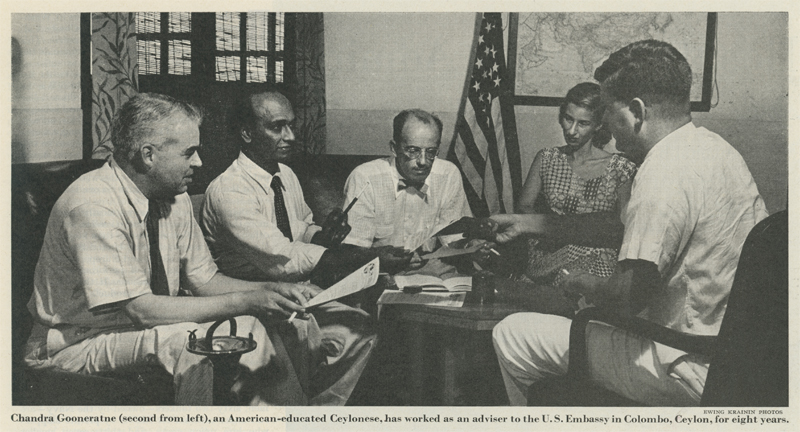

Several newspapers echoed that sentiment, describing Gooneratne’s "magnetic influence,"5 and "magnetic personality" which left attendees "spellbound."6 The imagery used to promote Gooneratne's lectures drew on existing stereotypes of India (note the Taj Mahal pictured on the pamphlet), and so too did the language used to describe him: "Magnetic," for instance, was a term partially associated with the American middlebrow fascination with the occult powers of Hindu yogis. A curious part of Gooneratne’s time in the U.S. is that he elided the fact that he was not from India, but from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), which he explained was his birthplace in an article from The Saturday Evening Post published in 1952. In "The Case of the Tan Stranger," writer George Weller profiles Gooneratne, who had returned from the U.S. and been stationed as an adviser to the U.S. Embassy in Colombo. The article describes in detail a Cold War diplomacy tactic, in which the U.S. State Department invited foreigners (including "union leaders, doctors, scientists, editors, teachers, and engineers") on a three or four month "all-expenses" paid trip to the U.S. in the hopes that they would proselytize for America when returning home. But this plan had a hitch. Weller writes, "For Europeans and South Americans these ‘leadership grants’ have worked out well"; but for leaders from Asia and Africa, dignitaries have "bump[ed] with brutal suddenness into our Southern American solution of the white-colored difference." In other words, these leaders had faced the racial policies of Jim Crow America:

"They discover, painfully, that they can enter some regional hotels, restaurants, swimming pools, and theaters only by protesting that they are not ‘colored,’ meaning Negro. This distinction they are too proud and too indignant to make. They arrive acutely color-conscious, full of memories of days when European colonialists applied the color line to social status in their countries. They go home, in some cases, stinging with the belief that America, too, is semicolonial."7In addressing this problem, Gooneratne reflected on his early experiences in the U.S. He described the sort of impression that wearing a turban could have on Americans: "Any Asiatic… can evade the whole issue of color in America by winding a few yards of linen around his head. A turban makes anyone an Indian," the article explains. And, in fact, there is a long history of African Americans who had similarly adopted the turban as a means of confounding the color line. Historian Paul Kramer describes the story of Jesse Routte, a New York-based pastor, who wore a purple turban and toured Mobile, Alabama, where he was invited by city hall officials, boarded trains, and treated as a foreign dignitary.8 Korla Pandit, a television star of the 1940s, was yet another example; born John Roland Redd, the son of a prominent African American preacher in Missouri, Pandit had passed as a Delhi native throughout his long television and recording career, wearing a bejeweled turban and becoming a fixture of the kitschy, mid-century musical genre known as "Exotica."9

Gooneratne, however, later distanced himself from adopting the turban he was constantly pictured with in Chautauqua lecture pamphlets and in his photos from the University of Chicago: "With a turban… you fly unmistakable colors. ‘But you miss,’ he warns, ‘the whole point of this game, which is to make the American know you and leave him as your friend for life.’" Gooneratne's commentary overlooks the different ways that the turban had also been a racial marker that has led to acts of violence against Sikh communities in North America from the 19th century onwards. But at some level, Gooneratne seemed to advise visitors to the U.S. to deliberately court confusion and misrecognition over their identities, if only to challenge the very premise of racial difference that governed the color line.

The Saturday Evening Post article continues with several anecdotes of Gooneratne encountering racism in the American South, and the ways he chose to use his deadpan humor to confront and circumvent the codes of Jim Crow.

On a "Southbound" train, Gooneratne sat in the "colored coach," refusing to be reseated in the white coaches when the conductor recognized he was not Black. "Are the seats better up there?" he asked, "Softer? Deeper? You must have better seats up there. Otherwise, why would you have mentioned my changing."10 Frustrated with Gooneratne’s line of questioning, the conductor marched away. Another time, at a railroad station in Jacksonville, Gooneratne was told by a boy scout that he would not be able to enter a "whites-only" waiting room. After having the boy admit that his complexion was closer to a pink geranium than a white handkerchief and his own skin closer in color to his tan shoes rather than black ones, Gooneratne slyly replied that that meant that neither of them, then, could enter, given that there were no "pinks only" or "tans only" rooms.

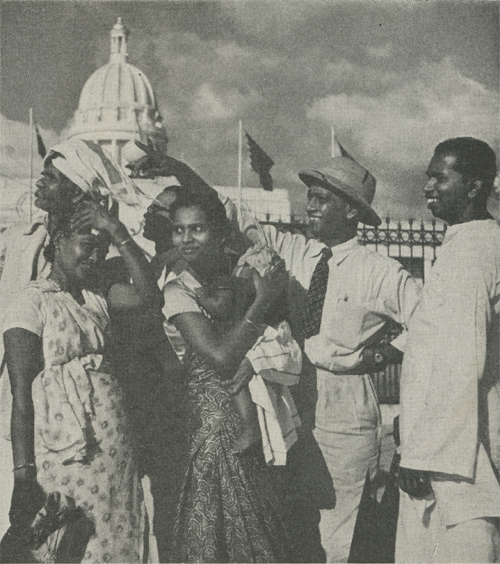

On a "Southbound" train, Gooneratne sat in the "colored coach," refusing to be reseated in the white coaches when the conductor recognized he was not Black. "Are the seats better up there?" he asked, "Softer? Deeper? You must have better seats up there. Otherwise, why would you have mentioned my changing."10 Frustrated with Gooneratne’s line of questioning, the conductor marched away. Another time, at a railroad station in Jacksonville, Gooneratne was told by a boy scout that he would not be able to enter a "whites-only" waiting room. After having the boy admit that his complexion was closer to a pink geranium than a white handkerchief and his own skin closer in color to his tan shoes rather than black ones, Gooneratne slyly replied that that meant that neither of them, then, could enter, given that there were no "pinks only" or "tans only" rooms.Throughout the article, the journalist Weller underscores the ways that Gooneratne tackled racism with "good humor," avoiding a "big crusade" against racism for the small challenges to racial logic he posed to Americans. And here, one wonders if such a deeply status quo approach was an effort to appeal to the taste and sensibilities of the middle-class readers of the Post. Yet reading the documents that trace Gooneratne's life in the U.S. suggests that his engagement with race and identity in America was, at the very least, a complex affair. From his days in Chicago onwards, we see the different ways Gooneratne was often misidentified along a vast spectrum of racial identities: from Indian to African-American, Hindu "yogi" to West African prince. Disidentifying with the racial codes of the U.S., toying with expectations of Americans, these were strategies that Gooneratne used in his effort to undermine, in a modest way, what he described as the inevitable role that visitors from Asia played in "the stratification of color."

1. See Elizabeth Station's "Scholar from Afar," written for the University of Chicago Magazine for more information about Gooneratne's life in Hyde Park.

2. "Sahib Chandra to Lecture on Poet of India." Forest Park Review 15 Oct. 1936: 1.

3. "Chandra Dharma Sena Gooneratne." The Pella Press 16 Nov. 1932: 1.

4. "Junior Choir to Sing at Chautauqua." The Hamilton Daily News 14 Aug. 1926: 7.

5. "Chandra Dharma Sena Gooneratne." The Pella Press 16 Nov. 1932: 1.

6. "Sahib Chandra to Lecture on Poet of India." Forest Park Review 15 Oct. 1936: 1.

7. Weller, George. "The Case of the Tan Stranger." Saturday Evening Post 12 Jul. 1952: 25, 103-104.

8. Kramer, Paul. "The Importance of Being Turbaned." Antioch Review 69.2 (2011): 208-221.

9. Smith, R.J. "The Many Faces of Korla Pandit." Los Angeles. June 2000: 72-77, 146-151.

10. Elsewhere, Gooneratne described a time in Ohio, when an African American cabdriver thought he resembled Fats Waller and assumed he was a Black performer from Harlem. Gooneratne found himself accidentally invited to a banquet, mistaken for their invited guest, the Prince of Dahomey.

Manan Desai teaches at Syracuse University and serves on SAADA's Board of Directors.