The Other Kamala

Kamala Harris and the History of South Asian America

By Nico Slate |

FEBRUARY 25, 2019

Will Kamala Harris become the first South Asian president of the United States? News coverage has focused on her unique racial history—her Indian mother is from Chennai and her father, who is Black, was born in Jamaica. Recently, U.S. media has also focused on whether progressive voters will be put-off by Harris’s past as a prosecutor and her reputation as something of a cautious centrist, closer to Hillary Clinton than Bernie Sanders. The history of South Asian America offers a way to connect Harris’s family history to her politics—and to rethink what it might mean to have the junior senator from California elected as our nation’s leader.1

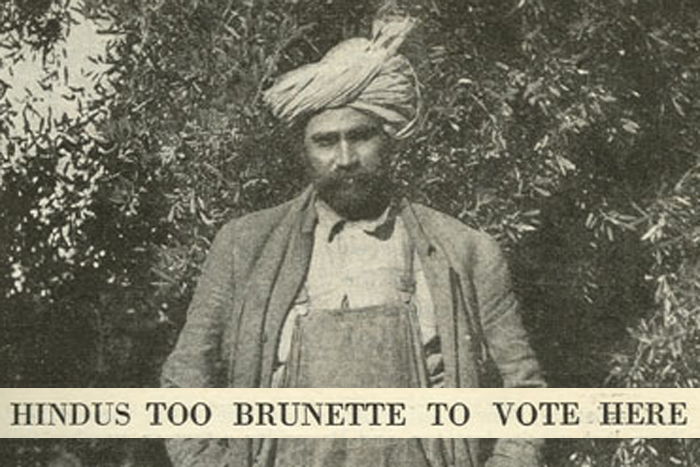

Let’s start with race. Like Barack Obama, Harris has managed to use her mixed racial ancestry to embrace multiple identities. Is she the first African American senator from California? Or the first South Asian American senator? Harris has claimed both identities, although only recently did her ties to India become widely-known. Some critics have suggested that Harris long downplayed her Indian roots. In an interview with the Washington Post, she dismissed such suggestions by saying that she had “been focused on the Indian community my entire life.” In any case, many Indian American leaders have, in the words of one report, been “eager to claim her.” Despite the growing media coverage of her Indian roots—and the current frequency with which Harris herself discusses those roots—an important facet of her South Asian identity has been largely ignored: the fact that her mixed-race heritage connects Harris to the long history of South Asian Americans who never fit neatly in any one racial box. Put differently, it’s not just her mother who links Harris to the South Asian community; equally important is the fact that she has had to find her way outside conventional American racial categories.2

Consider an episode in the remarkable life of another famous Kamala: the feminist and anticolonial activist, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay (often referred to by her first name, Kamaladevi). In the Spring of 1941, Kamaladevi boarded a segregated train heading across the American South. When the train conductor ordered her to leave the “whites-only” car, she refused. The conductor realized she was not African American and demanded to know “from which land she came.” Kamaladevi replied, “It makes no difference. I am a colored woman obviously and it is unnecessary for you to disturb me for I have no intention of moving from here.” The conductor muttered, “You are an Asian,” but he did not bother her again.3

Many antiracist activists and progressive advocates of criminal justice reform are rightly troubled by the role Harris played in supporting California’s longstanding criminalization of nonviolent offenses, her handling of wrongful conviction cases, and by several other facets of her career as a prosecutor. Whether or not it is possible for a high-level prosecutor to avoid perpetuating “the New Jim Crow,” there is good reason for Harris to face hard questions concerning her approach to criminal justice. As the law professor, Lara Bazelon, recently wrote in the New York Times, “If Kamala Harris wants people who care about dismantling mass incarceration and correcting miscarriages of justice to vote for her, she needs to radically break with her past.” Her efforts to present herself as a progressive champion of criminal justice reform will ring hollow so long as she does not forcefully admit her past mistakes. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that Harris has spoken out strongly against many forms of contemporary racism—from racially-motivated voter suppression to our draconian deportation policies. Compare her approach to race and racism with the policies of high-profile Indian American politicians like Nikki Haley or Bobby Jindal, or with the long history of South Asian Americans trying to claim whiteness in order to benefit from—rather than end—America’s racial hierarchy.5

Kamaladevi Chattopadyay was not alone in forging such solidarities. The prominent Indian American leader, Jagjit (J.J.) Singh became friends with the executive director of the NAACP, Walter White, and collaborated with White to oppose racism within the United States and abroad. Such solidarities extended into the civil rights movement. On May 27, 1964, Rammanohar Lohia, a member of the Indian Parliament, was turned away from Morrison’s Cafeteria, a “whites only” establishment in Jackson, Mississippi. The following day, dressed entirely in white, Lohia returned to Morrison’s. The manager told him to leave. Lohia replied, “I tell you with greatest humility, I am not leaving.” By forcing the police to arrest him, Lohia turned what had been a local story into a global scandal. The State Department sent a formal apology to the Indian Ambassador. The American Ambassador to the United Nations, Adlai Stevenson, offered his apologies. Lohia replied that the State Department “may go to hell” and added that Stevenson should apologize to the Statue of Liberty.

Lohia and Kamaladevi were both visitors to the United States—not migrants. But their efforts to forge solidarities with African Americans were matched by a range of Indian American leaders. Even more than J.J. Singh, the renowned Indian American activist, Taraknath Das, spoke out against racism. In a speech given on December 5, 1920, Das declared that the “freedom of all people is our ideal.” Some argued that “a color conflict could be won by the white-skinned men, if the Indian people can be won to the side of the white men.” Das rejected such an alliance. “Independent India will not be a tool,” he declared, “for those capitalistic, imperialistic nations whose business it is to subject men of another color and creed.” Das would have been proud to see Kamala Harris speaking out against racism at the Pratham Gala.7

Das’s speech took place at the national convention of the Friends of Freedom for India, a remarkable organization he cofounded in 1918 and that championed India’s freedom, along with the rights of Indian Americans. The history of the FFI offers a unique perspective on the career of Kamala Harris. Understanding this history—and its relevance to Kamala Harris—requires first discussing the three committed activists who founded the organization: Taraknath Das, Sailendranath Ghose, and Agnes Smedley. A Bengali scholar and revolutionary, Das fled India in 1905 to avoid imprisonment. After arriving in Seattle in the summer of 1906, he became the first Indian migrant to claim political asylum in the United States. He was 22 years old. To earn a living, Das picked celery and worked in a chemistry lab at Berkeley before landing a job as an interpreter for the American immigration service in Vancouver. In 1908, he began publishing a bi-monthly journal called Free Hindusthan. After the British government complained, American authorities offered Das a choice: stop publishing the paper or he would be fired from his position as an interpreter. He quit, and began traveling up and down the West Coast, urging his countrymen to rebel against British rule. Das alarmed British authorities by enrolling at a military academy in Vermont and encouraging other Indians to seek military training. After pressure from British officials and American military intelligence, the academy expelled the Bengali radical, ostensibly for making speeches against British rule. But despite British opposition, Das managed to gain American citizenship in June 1914.

You liberals and radicals of America, what are you doing about the Indian revolution? Where is your voice? Where, indeed, has been your voice while Hindu revolutionaries in your country have been sentenced to prison because they have tried to free their country from a foreign and autocratic rule?Ghose appealed for the support of “idealistic Americans,” and concluded, “We shall learn whether your idealism transcends racial and national boundaries.”8

Of the growing number of Americans who supported India’s freedom, none was more influential than the third founder of the FFI, Agnes Smedley. Born in Missouri in 1892, Smedley grew up in a small Colorado mining town. In early 1917, she moved to New York and found herself socializing with Indian radicals including Sailendranath Ghose. She became more committed to India’s cause, and was soon rerouting correspondence between Indian revolutionaries in the United States, Mexico, Germany, and elsewhere. She moved homes multiple times a year to evade surveillance. Despite such precautions, Smedley was twice imprisoned for her efforts.9

If the FFI had only reached a few radicals like Smedley, its influence would have remained small. But the organization attracted a variety of influential Americans. The executive board included ACLU leader, Roger Baldwin, birth-control advocate, Margaret Sanger, and renowned socialist Norman Thomas. Robert Morss Lovett, an English Professor at the University of Chicago, served as president. Many of these figures were committed to a world free of colonial oppression and to an America welcoming of immigrants. The FFI called upon the government “to protect the traditional right of asylum for political refugees on American soil and to sever all connection with the British agents seeking to prosecute those representatives of the Indian people who are lawfully presenting their cause to the people of the United States.”10

Chief among the political wins secured by the FFI was its intervention into the British Empire’s forced labor practices. In the fall of 1920, a group of South Asian workers were arrested at the Bethlehem Steel factory seventy miles north of Philadelphia. They were taken to Ellis Island to be deported. Rather than send the workers back to India, however, corrupt immigration officials arranged for them to be forced into labor on a British ship. When the workers learned of these plans, they refused to leave the detention center. One was a naturalized American citizen. Still, all the workers might have languished in jail if word of their plight had not made its way to the FFI. FFI lawyers secured freedom for the workers, and unearthed what a newspaper called “a gigantic conspiracy between powerful British shipping interests and certain American immigration authorities to shanghai Indian workers out of this country.” Between 80 and 100 Indian immigrants had been forced into labor on British ships. But legal action and political pressure from the FFI put an end to this illegal system of forced labor.11

In the hundred years since the founding of the FFI, rarely has its legacy been as relevant as it is today. Immigration is now at the center of our national debate, thanks to a president who has built his political career on demonizing migrants. There is a troubling gap between the amount of media coverage focused on “the wall” and that given to the complexities of immigration—its causes and consequences—as well as the lived experience of those fleeing desperate conditions in search of a better life. The history of immigration has remained particularly obscure. We have gilded memories of European migrants arriving at Ellis Island, but what is more instructive at this current moment is the history of groups like South Asian Americans—long deemed racially undesirable, even while their labor was coveted. By fighting for their own rights, South Asian Americans created a legacy of struggle that points toward a more humane approach to immigration, a legacy advanced one hundred years ago by the Friends of Freedom for India and today by Kamala Harris. But it is not just her stance on immigration that links Harris to the FFI.12

The political nature of immigration leads to the second key lesson offered by the history of the FFI: that to resist nativist xenophobia requires building coalitions that cut across the social and political spectrum. Some of the Americans who supported the FFI were radicals like Agnes Smedley who envisioned a world beyond borders. Others were cautious liberals, eager to reform the system rather than to replace it. The FFI found success by working across such divisions. Coalitions are not easy to build or to sustain. But the more egregious the injustice, the easier it becomes to rally a range of actors in opposition. Perhaps that is the most important lesson of the FFI—that we must seize this moment as an opportunity to build solidarities across borders of many kinds. Will Kamala Harris campaign for that kind of border crossing? Will she be able to bridge the divide between the progressive left and the political center? Those troubled by some of the decisions she made as a prosecutor and by her cautious centrism will demand evidence that she is willing to take risks to stand up for real justice. More than her racial heritage, her words and actions will determine the degree to which Harris can build on the long history of South Asian Americans who fought for a country in which everyone could vote, gain citizenship, or perhaps even become president.

Also watch, Anjal Chande's Out of the Shadows, A Colored Solidarity, which tells the story of intersecting social movements in India and the United States through the lens of Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay's activism:

1. Ryan Cooper, “Why leftists don't trust Kamala Harris, Cory Booker, and Deval Patrick,” August 3, 2017.

2. Kevin Sullivan, “‘I am who I am’: Kamala Harris, daughter of Indian and Jamaican immigrants, defines herself simply as ‘American,’” The Washington Post, February 2, 2019; Katie Glueck, “Inside Kamala Harris’s relationship with an Indian-American community eager to claim her,” December 19, 2018.

3. Nico Slate, Colored Cosmopolitanism: The Shared Struggle for Freedom in the United States and India (Harvard University Press, 2012); also see Anjal Chande's "Out of the Shadows, A Colored Solidarity."

4. Sunita Sohrabji, “‘Let’s Speak Some Uncomfortable Truths’, Sen. Kamala Harris Tells Sold-out Crowd at Pratham New York Gala,” October 5, 2018,

5. Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: New Press, 2012); Branko Marcetic, “The Two Faces of Kamala Harris,” Jacobin; Lara Bazelon, “Kamala Harris Was Not a ‘Progressive Prosecutor,’” The New York Times, January 17, 2019.

6. Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance, and Indian Anticolonialism in North America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014); Doug Coulson, Race, Nation, and Refuge: The Rhetoric of Race in Asian American Citizenship Cases (SUNY Press, 2017).

7. “International Aspects of the Indian Question,” The Independent Hindustan 1, no. 6 (February 1921), 130-131, available via SAADA.

8. Sailendranath Ghose, “India’s Challenge to American Radicals,” Young Democracy (June 1, 1919), available via SAADA.

9. Janice R. MacKinnon and Stephen R. MacKinnon, Agnes Smedley: The Life and Times of an American Radical (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988); Ruth Price, The Lives of Agnes Smedley (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

10. “National Convention of the Friends of Freedom for India,” Independent Hindustan 1, no. 5 (January 1921): 113-115, available via SAADA.

11. Basanta Koomar Roy, “Doing England’s Dirty Work,” Independent Hindustan 1, no. 2 (October 1920), 27, 29, 39, available via SAADA.

12. Mae Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004).

Nico Slate is a Professor of History and Director of Graduate Studies at Carnegie Mellon University. His research and teaching focus on the history of social movements in the United States and India. Slate is the author of Lord Cornwallis Is Dead: The Struggle for Democracy in the United States and India (Harvard University Press, 2019) and Gandhi’s Search for the Perfect Diet: Eating with the World in Mind (The University of Washington Press, 2019). Portions of this essay are taken from Lord Cornwallis Is Dead.