Since then, Hari Kondabolu has been all over the web and television, appearing on Conan, Comedy Central, and most recently FX's Totally Biased with W. Kamau Bell and the "Untitled Kondabolu Brothers Podcast." He has quickly emerged as one of this generation's sharpest comedic voices on the illogic of race, xenophobia, and representation. Hari took some time to chat with SAADA about growing up in Little India in Queens, performing "the accent," and how Paul Mooney helped him find his comedic voice.

MD: I should tell you first, I teach an Asian American literature and culture class, and we've been watching quite a few clips of yours. Right now, I'm reading about

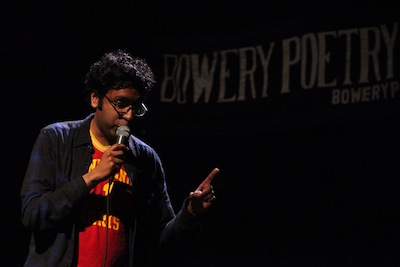

Photo by Mindy Tucker

Photo by Mindy TuckerHK: The White Guilt vs. Racism -- that one?

MD: Where a white person witnesses a brown person being profiled in an airport, feels guilty, and clutches onto their bell hooks very tightly. The students were really into it.

HK: Yeah, that's one of the more polarizing clips that I've done. I get emails, praise, and hatred on that.

MD: Has bell hooks chimed in at all?

HK: No, bell hooks hasn't chimed in yet. I have another joke that I've been doing that has bell hooks in it, where I name a fictional daughter bell hooks Kondabolu. It should be noted that I’ve never met bell hooks, but I’d very much like to.

MD: So, how did you first get into comedy?

HK: I always loved comedy and stand up was always exciting to me. I remember seeing Margaret Margaret Cho had a special where she was in a leather body suit -- an hour special, I think -- and I remember watching that a ton when I was a kid. It was the first time I saw someone who wasn't White, Black, or Latino doing stand up.Cho do stand up on TV. This was back when Comedy Central didn't have that many programs, so they'd air the same things over and over. Margaret Cho had a special where she was in a leather body suit -- an hour special, I think -- and I remember watching that a ton when I was a kid. It was the first time I saw someone who wasn't White, Black, or Latino doing stand up. She was talking about her parents and her experience, and the idea that that was something seen as valid made me think, this is something I could do. So I started writing, and I did comedy for the first time in my high school. As a 17-year-old I started a comedy night, and it's been an obsession ever since. I did stand up in college, and I'd do open mics in New York when I got back from break. However, I moved to Seattle after college and that was my first true scene, and where my career started.

MD: You hear a lot from comics about how humor was a way of dealing with being picked on, or dealing with feelings of alienation. Did that ring true for you? When you were growing up, were you that funny kid who used jokes to deflect discrimination?

HK: I was a funny kid, but I wasn't a class clown. I think it was Billy Crystal who talked about the idea of being a class clown versus being a class comedian. I definitely saw myself as a class comedian. I didn't interrupt class but would comment off other comments, or I'd take information and have something funny to say, as opposed to just making sounds or imitating or saying something that poorly thought out. Certainly among my friends and family I was funny, but I wasn't necessarily the funniest. My friends are still a lot funnier, and my brother Ashok is exceptionally funny. He's still the person I find funniest in the world, and sometimes I feel I'm doing an impression of him onstage.

MD: From what I've seen of him, your brother’s humor has a kind of absurdist tendency.

HK: Yeah, he definitely has an absurdist tendency. He loves Adult Swim stuff. But you know, that developed over time. I have elements of that too but not like my brother. What I do onstage isn't When you grow up watching those TV adaptations of Hindu epics like Ramayana or Mahabharata, you get a taste for the absurd. necessarily the same as what I laugh at all the time, know what I mean? I'm starting to incorporate more of myself into my stuff. But my stage voice and what I laugh at isn't necessarily the same.

Regarding absurdity and humor, I've been thinking about this more recently. When you grow up watching those TV adaptations of Hindu epics like Ramayana or Mahabharata, you get a taste for the absurd.

MD: [Laughs] Right, those battle scenes were pretty amazing.

HK: And the ridiculous faces you see. It’s coming from a theater tradition that's being translated poorly onto film. Heads are being chopped off, but the producers don't have the ability to do it well so you'll see part of the green screen. So, you watch all this stuff nowadays on Adult Swim; production done poorly now on purpose. At the time, those Ramayana and Mahabharata serials were the only way we could represent these epics -- it wasn't meant to be hilarious, obviously. It was seen as a religious thing.

But it was hilarious. And you know, we come from that. Me and my brother come from watching stuff like that so certainly that had an impact on what we find funny. It is funny.

But your question about alienation. Certainly, certainly I felt that. When you grow up South Asian, especially 20 or 30 years ago, you're seen as a freak in a way. Me and my brother a little less so because we grew up in Queens. We were around other South Asian people, so we had safe spaces. We had the family party where all the kids would hang out, even though we weren't really friends, just put in a situation where our parents would meet. We would talk about stuff we couldn't always talk about because we didn't always have brown people around us. And again, it was a little less so for us, because we grew up in Jackson Heights -- little India -- and then we lived in Floral Parks, Queens which has a big Indian community, especially a big Malayali community. We're Telugu, but we had a lot of South Asians around us constantly. So we had those jokes that would be insider community jokes that we'd hear outside. We had the ability to laugh at how we were in this weird place.

It's funny. I did this piece on Totally Biased during the first season. It was a bit about Mindy Kaling getting a TV show, and how far we've come as South Asians. When I was writing the piece, it initially felt corny -- 'cause I'm talking about Apu, about Fisher Stevens, the dude from Short Circuit, and I've been talking about this kind of stuff casually for a decade. I was writing and thinking, "This is corny. Do I really want to do this?" But when I was telling people around the office about the piece, I realized they'd never heard this. I've talked about this for a decade, our friends have been talking about this for a decade plus. Apu has been corny to us for a really long time. But in mainstream American society, this has never been discussed before. Hank Azaria and The Simpsons have never been called out.

So when Hank Azaria tweeted to me recently, "it was great to hear a crowd wildly cheering the idea of me getting my ass kicked,” that was really big deal to me. Holy crap, the guy who does the voice that tormented us for years is responding.

MD: That was actually a question I had: What's the current status of the Azaria-Kondabolu beef?

HK: I mean, c'mon, there's no beef. I was surprised he wrote and I replied and said, "Well, we're even now." I don't see it as a beef, and I don't think he saw it as a beef. I get it, you know? There's an interview where he talked to the producers of The Simpsons and said something like, “I don't really do a good Indian accent. Mine's kind of a stereotype.” They said, “Oh, it doesn't really matter.”

Because it didn't! That's the point. We didn't matter. We were non-entities. But there's a generation of us who grew up watching that, and we can talk for ourselves now. We can say that we were haunted by that, to a certain degree. We were called "Apu." We had to hear that impression. And they didn't expect to hear from us who'd grown up here and have a stake in this and who have identities that are more complicated. Now we can say, yeah, Apu is a racial stereotype. It's minstrelsy. That's not to say the show isn't funny or Apu doesn't have interesting characteristics or can't be complicated in certain ways. And that's not to say The Simpsons isn't brilliant, or that I don't love the show.

Doing comedy informally and stand up formally allowed me to talk about experiences that a lot of people haven't been allowed to talk about.

I remember going to comedy clubs when I was a young person and being made fun of. Me and my brother would be seated in the front row, wondering why we were always in the front and why the comics were making fun of us. We were being planted up there to be fodder for them. We were told, "Can't you take it? There was never someone who represented us who could give a response. This generation is the first that's been able to give a response to that sense of alienation, of being targeted.Can't you take a joke?" It's not that we couldn't take a joke; it's that there was never a response. I'm not even talking about heckling. There was never someone who represented us who could give a response. This generation is the first that's been able to give a response to that sense of alienation, of being targeted. We've never been able to swing back. So certainly, my comedy is part of that response. And I think everybody's comedy is -- you're responding to your world, you're giving your worldview, you're responding to things that have happened in your life. That's part of comedy, and the best comedy comes from that truth. This is the first generation that has been able to talk about the South Asian American experience.

MD: In another interview you'd said that 9/11 was a seminal moment both for your politicization and for your approach to comedy. How did those two things change after 9/11?

HK: I wasn't really a political being before that. I was in Queens in a very diverse setting, and certain things I took for granted. I didn't think racism wasn't a problem, but I don't think I really understood how it played out institutionally. When 9/11 happened, I saw the complexity of racism. I heard about brutal hate violence throughout the country and in Queens, which shocked me, 'cause I grew up here and wondered why would it happen here. I could understand somewhere in the middle of the country where there weren't many Brown people and people are ignorant. But here? I didn't realize this hatred and ignorance was everywhere. Just because you're around many different types of people doesn't mean you know anything. There are very segregated neighborhoods in Queen.

You'd read about the deportations, about the government targeting people, and how the SIkh community was targeted, how Muslims in general were targeted by both the government and other Americans. That was hard and I didn't understand it.

I went to college in Maine. Maine was the first time I got the gaze. I was seen as an outsider when I got there. The way people would look at me or the questions people asked me weren't questions I really got in New York. For instance, the question “where are you from?” In New York, I could answer India to that question, because everybody was from somewhere. When I asked a white person in New York where they were from, they would answer Greece or Italy, or "I'm Jewish" or Irish. Even if they really weren't and were two or three generations removed, they'd know how to answer that. In Maine, I was seen as an “other.” They wanted to hear India, but I wouldn't get their complex identities back. That was irrelevant. I was the outsider.

So I sensed in that setting and after 9/11 that this wasn't the country I'd thought it was. I started to take more courses on race, on human rights and politics. I definitely became more informed. I had a roommate from Seattle, who'd gone to a small progressive private school and came with all these radical ideas. He was a very politicized white dude. When I was a Freshman I just wanted him to shut up. I didn't know what he was talking about. I didn't know what School of Americas was nor did I care. After 9/11, hearing him talk made more sense. He's one of my best friends, and he was a big reason I moved to Seattle to organize.

I became a more politicized figure in college, someone who wanted to make noise. At the time, my comedy certainly didn't reflect that. So I started to write about things that were not necessarily funny at first, you know? I think I tried to make them funny, but they were really ranty and preachy, and didn't have my true voice in it. But I was figuring it out.

I'd seen Paul Mooney do stand up in Washington D.C. Mooney had written for Pryor and was this incredible figure that I hadn't heard about before because he wasn't mainstream. He played to mostly Black and minority audiences. Chappelle Show brought him back to the mainstream but he still wasn't a mainstream figure, wasn't huge, even though he was so instrumental to Pryor's success and to In Living Color. Watching him be so raw in two hours and talk about race and be hysterically funny was cathartic for me and made me question everything I did as a performer. I think I tried to be him for a year -- I was trying to be an older Black man onstage. I didn't understand what my voice was. It took a long time to realize I could talk about race from my experiences, from my heart, that there were things about the

South Asian American experience and about race that were different than what he spoke about. Also my tone was never as brutal as his. I tried but I realized I like being absurd and silly. I had different tones, and I wasn't using them. Seattle helped me find the diversity of my voice.

South Asian American experience and about race that were different than what he spoke about. Also my tone was never as brutal as his. I tried but I realized I like being absurd and silly. I had different tones, and I wasn't using them. Seattle helped me find the diversity of my voice. The first joke I wrote where I felt, "this was me," was about the Koh-i-Noor diamond and the British "finding it" in India. That was the first time I was in DC. I was interning for what was then called the Indian American Center for Political Awareness and Senator Hillary Clinton. I was around different kinds of Indian kids -- some very politicized -- and that led to amazing conversations. After being in that setting and seeing Paul Mooney, I wrote a joke which was the first time I thought, "Okay, this is who I actually am. This is what I actually believe."

There's something about using anger on stage that appeals to me. It didn't make sense before when I was using it, because what really was I talking about? This joke touched on something I cared about. Colonialism was something that wasn't really discussed in stand up, and it was important to me and was part of my experience as someone of Indian descent.

MD: Were there other comics who helped you make that transition?

HK: Marc Maron. When I was in New York clubs to watch comedy, like in the Comedy Cellar, Maron was the one who always stood out. There were different styles and stuff, but I couldn't remember their stuff as well. Maron I remembered. Maron hit me on a level even as an 18-19-year-old, where I was like, this is so much deeper. These aren't just jokes. He's talking about pain that I don't quite understand or haven't lived yet, but knew was personal and important. I didn't know you could do that. Marc Maron was huge.

David Cross had this double disc called Shut Up You Fucking Baby! which came out right after 9/11. Listening to the record now, some of it feels dated, like this is just ranting about post-9/11 stuff and Rumsfeld. But at the time, nobody was doing that. The Daily Show did that for years. But Cross was really one of the first who put it on a disc, and at the time, I thought, wow, this is a guy whose really digging in, and it's so raw. I obsessively listened to that double disc.

Certainly Pryor. The Bicentennial record in particular.

MD: The last track on that record is amazing.

HK: It's so great. It’s the first time I realized that everything didn't need to be hysterically funny. Things can have different tones and timing, and have different meaning and it's all part of a whole act. That last track shook me, and made me realize that comedy can be poetry too. It doesn't necessarily all have to be straightforward set up and punchline jokes. That meant a lot.

There's a lot of people, you know? Carlin and Hicks, they're all floating in there. Lewis Black -- you know, I've realized more and more, Lewis Black is a big reason why I yell punchlines and feel free to show emotion on stage. Stylistically, we're Right now, the biggest influence on me is a British comic named Stewart Lee, especially in terms of the form. I've learned so much from watching his pacing, and knowing that everything doesn't have to happen to immediately.different, but when I was in high school and college, I loved watching Lewis Black on The Daily Show.

Right now, the biggest influence on me is a British comic named Stewart Lee, especially in terms of the form. I've learned so much from watching his pacing, and knowing that everything doesn't have to happen to immediately. I like to be punchier than he does, but it’s been good learning from him, while also learning how to maintain my own voice.

One thing I've realized from Mooney, from Stewart Lee, from Marc Maron is that I might not be for everybody and that's okay. I think my style can seem strange to some South Asians since there was just Russell Peters for a while. That was the name I kept hearing. My experience and what I found funny was so far from that. That's not to disrespect Russell Peters, but what he did wasn't what I wanted to do. So to keep hearing that name was always confusing, because it's like, this dude's a decade older than me and from Toronto, and you're telling me I'm supposed to be like him when that's not who I am. It's foolish, but you'd hear that, not only from Aunties or Uncles but from younger people who've just discovered comedy from him. It's exciting to be in this current era where there are so many different voices. You have me, and Aziz, and Kumail Nanjiani, and so many others doing interesting and very different things. And of course we are, because really, why would be the same?

Considering how far we’ve come, it’s weird to still read for certain parts that are stereotypical. Actually, not even read, since I refuse to read the part of cab driver characters, or an ex-accountant. Just getting a script from someone who’s interested me in that kind of role is strange. Dude, look at me. If you're going to stereotype, maybe I'm a professor, but I'm not a computer science dude. I'm teaching American studies, you know? That's what I am. I don't know shit about computers. There's a generation of us who did Youth Solidarity Summer.

MD: You did YSS?

HK: Yeah! We were influenced by Vijay Prashad. There's a generation of us like that. Why are we being grouped with that other shit? If anything, I'm a different archetype. [Laughs]

MD: Was that film Manoj partly a response to that idea, that audiences expected you to be a particular kind of comic?

HK: Yeah, certainly. It's been nice that Manoj still gets talked about, and people bring that character up. I think it's getting a little dated now, which is good. It should be because it was made six years ago. Which is crazy because I'm getting old as well. I mean, hearing that students writing papers about me…

MD: [Laughs] I thought that might weird you out.

HK: It's not weird, it's flattering. I'm not that old, but it goes to show that this is so new still. I know that I'm one of the first South Asian comics. But yeah, it is strange.

MD: I've shown Manoj to my classes, and I don't usually tell them it's a mockumentary. I let them wrestle with it on their own. I remember one student -- an African American student -- who said it made her uncomfortable, because at some point she didn't know what she was laughing at. I know you've mentioned before that the power of stand up is that it puts people in a position of discomfort, where they have to deal with that discomfort. Could you say a little bit more about that?

HK: Part of stand up is about surprising people. And I love using discomfort, because you're made to feel uncomfortable about something and you're put in this place where you're questioning yourself. Then suddenly a comic makes you laugh and you're in a very different spot then you were right before. I mean, you come to a comedy club to laugh, are suddenly made to feel uncomfortable, and then laugh out of somewhere else? To me, that is good. It's working on two levels.

That's what the great comics did -- talk about pain, about oppression, about things that are not easy to discuss -- and find ways to discuss them. Maybe people don't laugh immediately because they don't know what to do with these feelings, but then, if you're good enough you find a way. Sometimes people laugh because I've hit something that resonates with them on a deeper level. Sometimes people laugh because I said it in a funny way, and they don't even know what I'm saying. Comedy is complicated. I'd like to believe I'm hitting people exactly the way I want to hit them, but sometimes people think the face I'm making is funny. For the people who do get it, it's rewarding. I'm hopefully giving you something I wish I had ten years ago -- the comic I wish existed ten years ago. That makes me feel good. I feel proud of what I'm doing now.

I wish I could push it further. I definitely want to be more personal. I've been grappling a lot with talking about my parents in my act, because I think their experience is really unique, and funny, and interesting. But historically the way that has looked to me is simple and degrading. And I also feel like there's this fear that if you talk about your parents in a mainstream setting you're seen as a hack. That bothers me. Parents are a major part of anyone's life experience, whether they're present or not. So, why can't we talk about our folks? I think there's something very important in the fact that they're immigrants, and that they struggled here, and they had adjust to a new place and raise I know Desi comics that use the accent, and I think some of them do it recklessly. I know folks who do it who say they’re just trying to be accurate about how their parents sound. I get that, but for me, I don't want to do it in a mainstream setting. I'll only use the accent when I'm amongst mostly Desis doing a South Asian show.kids who are American when they’re not. What matters is how you talk about them. How do I give my parents' dignity and still talk about the complicated experience of growing up with parents who didn't grow up here?

I know Desi comics that use the accent, and I think some of them do it recklessly. I know folks who do it who say they’re just trying to be accurate about how their parents sound. I get that, but for me, I don't want to do it in a mainstream setting. I'll only use the accent when I'm amongst mostly Desis doing a South Asian show. I don't do that many, but when I do I have fewer issues doing the accent. Suddenly I'm back in my room with all my parents' friends' kids, and we're joking around like when I was eight, nine, ten. Again, we weren't friends, except we were all brown and thrown into this situation so we knew how to laugh. When I'm on stage I feel like I'm in that setting again. Outside of that situation, I feel uncomfortable using the accent. I want you to laugh at the story, at the experience, not at my parents.

It also makes me wonder, when my father talks, are people laughing at him behind his back? My mother and father struggled in this country. My father communicates fine, but he has a thick accent, and his grammar isn't always perfect. He has had to deal with that, and that takes an incredible amount of strength. So for him to be made fun of -- "my father sounds like this, and this is how he says these words" -- it's funny to us, certainly, as a family, or in our community. But in the real world, this hasn't been easy for him.

MD: Is it partly that we're not in a place that a South Asian or South Asian American comic can use an accent and not have it be the butt of the joke? Does the accent overwhelm the comedy?

HK: I don't know, man. I don't know how to respond to that because I'm uncomfortable with it in general. I saw Life of Pi yesterday -- hadn't read the book -- saw the film in 3D, and thought it was great. I read Himanshu [Suri]'s article on it, and agreed with him. It was one of those things you go to, just waiting to be pissed, and you're like naw, it's good. It's beautiful, in fact. The screenwriter was there, doing a Q & A afterwards. He'd adapted it from the book. That was fine -- I was a little annoyed by the fact that he didn't say the main actor [Suraj Sharma]'s name at all. The kid was the movie. It was his acting that was the extraordinary thing. Why aren't you saying his name? The screenwriter [David Magee] kept referring to him as the younger version of the character, and I was thinking, say his name, dude. He's not just some actor, he's the dude who makes this thing.

At some point he was doing an impression of him. He was talking about some experience he had with a South Asian person, and he used the accent to mimic him. And even in the film, the white dude in the film who plays the author trying to find his story does an impression. It made me uncomfortable. Would that story be interesting without the accent? Were people laughing because of the accent? And the story wasn't even that witty -- so what is it?

MD: I was thinking about the two legendary comics, who did do accents in a way that seemed respectful: Lenny Bruce and Richard Pryor. I remember listening to a Lenny Bruce record doing all these voices that he heard in New York. Even Richard Pryor, with his characters Mudbone and the Wino. They always risked poking fun at their own marginalized communities, yet they were able to play those accents in a way that felt like they were celebrating or being honest about their communities. I don't know if South Asian comics and artists can do that right now.

HK: With Richard Pryor it's different as a Black comic performing in front of a lot of Black people and sharing a very complicated experience. And the history of African Americans in the U.S. is so different for South Asians. So for Pryor it's very different. He also talked about race very critically. I mean, if you're going to do the accent, you better talk about race critically too, right? Otherwise, you got the laugh, but is that it?

And Lenny Bruce took ownership -- he was doing a lot of cutting edge things. Still, I don't love everything that my heroes have ever did. So with Bruce, it's the same thing. There might be things he did that I think were incredible, and other things where I'll think, you know, I wish a gay dude was able to say that instead of you. Especially, in that era, a progressive comic who is pushing boundaries, and not just political humor like Mort Sahl, but someone who is really pushing it. I wish we were in an era where a gay dude can say that. As a brown person, I want to speak for me as a brown person -- I don't need a white dude to speak for me. I appreciate your allyship, but I'd like to do it myself. So in terms of accents, I think it's complicated. It depends on how you do it. I can't speak for everyone, but for me personally I have a complicated relationship to it. I still get offered parts for really degrading characters that involve accents, and I can't even go into the audition room.

MD: A year ago, you went on the Make Chai, Not War tour. What was that experience like and how did your audiences respond?

HK: First of all I should say I didn't come up with the tour…and the name. And that's not disrespect, but that's Azhar [Usman] and Rajiv [Satyal]'s group. They were very kind to bring me with them, and I appreciate it.

It's very complicated because India never was and never will be just one place. Each city and town we performed in was very different. Performing in Patna and Durgapur isn't the same as performing in Kolkata and Mumbai -- audiences have very different expectations, or for that matter, no expectations. In Patna, English is not as widely spoken, and I was read as a South Indian. In Bangalore, I was read as a South Indian, but that means something very different over there. When we performed in Hyderabad, there was excitement as soon as I said something in Telugu to open. So each show was different. Mumbai and Kolkata were easier. There was a broader range of things I could talk about -- like American pop culture and Indian American representations -- and there was both an interest and understanding and a fluency. Whereas when I had do something in Patna, it was harder. I'd have to speak slower, and I lost a lot of material. So yeah, it was extremely complicated. You'd never know how to prepare for one show. It felt like I was open mic-ing in front of a thousand people, 'cause that's essentially what I was doing. 'Cause even though some of the stuff was tried and tested, doing something in India is very different. It was a great experience and something I don't think I'll ever have again. Maybe I'll perform in India again, but not in front of thousands of people. It was extraordinary.

I also saw that there were local scenes. There's a local scene in Mumbai, a local scene in Chennai, in Bangalore, in New Delhi. And each place has a different culture, tradition, and different venues. In Chennai there's more of a theater tradition, so there's more infrastructure. In Bangalore there are more expats, so it was easier to get started. In Mumbai it's huge, and they have a comedy club. There's the two big guys -- Papa CJ and Vir Das – from Delhi and Mumbai respectively, who started in stand up, and now are in big films. It was also incredible to see American and British influences in Indian standup.

It's funny because with South Asian American comics there was all that hacky stuff early on with accents. There's so much simplification of the experience for mainstream white audiences, especially early on. Post-9/11, there was a surge of brown comics and they were talking about shit like that. And going to India I maybe expected similar things, but naw, man, within a few years you have brown comics talking about politicians, the prime minister, political parties, because they're performing in front of brown people. I mean, it's also somewhat self-selective audience because you have a growing middle class, people who speak English and can afford to buy tickets to a comedy show and willing to spend money on that instead of going to the cinema, or a million other things. But very quickly, I feel like they’ve grown a complicated scene. It's still new though.

MD: I know the past two years have been huge for you with Totally Biased and the Comedy Central special. What are you planning for 2013?

HK: This year I want to focus on my stand up as much as I can. I've been wanting to make an album for a couple years and I keep backing down, thinking I'm not ready. This year I want to push forward and get it done. People keep asking, "Do you have a record? I want to buy something," and I don't. A lot of it is just me thinking, "I'm not ready, all this stuff doesn't flow" but sometimes you have to just force it and put it out there. There are people who want to support you and think your work is worthy, and they want a compilation of your material. For those people who haven't seen me do an hour, doing an hour is a very different thing than doing ten minutes or seeing a clip on the internet. In an hour set you have to gather a bunch of ideas, you can wander, you can make choices, you make mistakes and have to dig yourself out. I'm a much better comic in a longer set. Any comic worth their weight is better in longer sets because you fill in your personality and the audience knows you in a much more complete ways. I'm a much more complicated person than I can express in ten minutes.

MD: Yeah, the first time I saw you was at the University of Michigan for a Human Rights colloquium. You did an hour set, with a Q & A afterwards.

HK: There was a vegan dude that night that grilled me on my vegan soul food bit! That joke I've disowned somewhat just because I found out that vegan soul food was a bigger movement championed by black folks like Bryant Terry in Oakland. It was a way to create healthier cuisine especially for the African American community. I think there's still some points in it about cultural appropriation that might work. Who's eating it? Who's starting restaurants? But it's certainly much more complicated than that joke. I wish I did more research before I told it.

It's weird 'cause I still get grilled by vegan folks. I'm like, that was four years ago, I've grown! And I've apologized.

MD: What's funny is that the comic Dick Gregory was a big food activist himself, and wrote a book on healthier living.

HK: That's the thing. Points of view change, and you learn. I'm a person and some things are still with me, and some things I've dropped. What's hard as an artist is that people see you grow on stage. And certainly if people see the older clips on the internet versus the newer stuff, I'm different. My pacing is different, the stuff I talk about is different. I still talk about race a lot, but I talk about a whole bunch of different things. It's been interesting recently talking about sex and sexuality, and I know I'm losing some people on that, but gaining others.

I'm 30. I've lived a life, and that's part of who I am. That's hard, I think for some people in the audience who are expecting certain things and getting other things. But you know, that's art.

Manan Desai teaches at Syracuse University and serves on the Board of Directors for the South Asian American Digital Archive.